Nationally, there is a scarcity of health care professionals in rural communities across nearly every level and type of health care workforce.

By 2030, there will be a shortage of more than 17,000 primary care physicians.

The Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) National Center for Health Workforce Analysis

The American Nurses association has indicated that the national nursing shortage has reached a critical state. While workforce shortages occur across the U.S. including in urban areas, they are more pronounced in rural areas.

More than three in five primary care health professional shortage area (HPSA) designations are in rural or partially rural areas.

National Rural Health Association (NRHA). (2024). Addressing the National Rural Health Care Worker Shortage with a Focus on Kindergarten Through 12th Grade Educational Strategies.Although national data on women’s health and outcomes according to residence are limited, disparities in rural women are apparent. General health conditions and behavior that U.S. rural women experience at higher rates than their urban counterparts include, self-reported fair or poor health status, unintentional injury and motor vehicle-related deaths, cerebrovascular disease deaths, suicide, cigarette smoking, obesity, difficulty with basic actions or limitation of complex activities and incidence of cervical cancer. Other comparisons show that death rates from ischemic heart disease in rural women exceed that for all U.S. women. In some regions of the country, women in nonmetropolitan areas have higher rates of heavy alcohol consumption.

Proportionately fewer rural women receive recommended screening services for breast and cervical cancer.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. (2014). Committee Opinion No. 586: Health Disparities in Rural Women“Rural African American, Hispanic, Asian, and white women are less likely to have cervical cancer screening. African American, Hispanic, and white women are less likely than their urban counterparts to have mammograms. Comparisons of female patients in whom invasive breast cancer was diagnosed in Georgia from 2000 to 2009 indicate that women living in small rural and isolated areas were 30% more likely to have surgery and 17% less likely to receive radiotherapy as first-course treatment than their urban counterparts. Also, within these rural areas, African American patients were 57% less likely to have surgery than white patients." (American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (2014), Health Disparities in Rural Women, Committee Opinion No. 586.)

The 2019 age-adjusted natural-cause mortality (NCM) rate for the prime working-age population (aged 25–54) was 43 percent higher in rural (nonmetropolitan) areas than in urban (metropolitan) areas. This is a shift from 25 years ago when NCM rates in urban and rural areas were similar for this age group. (Thomas, K. L., Dobis, E. A., & McGranahan, D. A. (2024). The Nature of the Rural-Urban Mortality Gap (Report No. EIB-265). U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service.)

“The magnitude of the difference between rural and urban mortality rates in 2004 (913.13 vs 836.16) resulted in 76.97 excess deaths per 100 000. It increased in 2016 (847.65 vs 712.95) to 134.70 excess deaths per 100 000. This reflects a 75% increase in the rural penalty in the past 12 years. By extending the 134.70 excess deaths occurring in rural America to the entire rural population in 2016 of approximately 45 350 000, the nation was experiencing about 61,000 additional deaths that would not have occurred if rural America had been able to achieve the same improvements as urban America.” (National Library of Medicine)

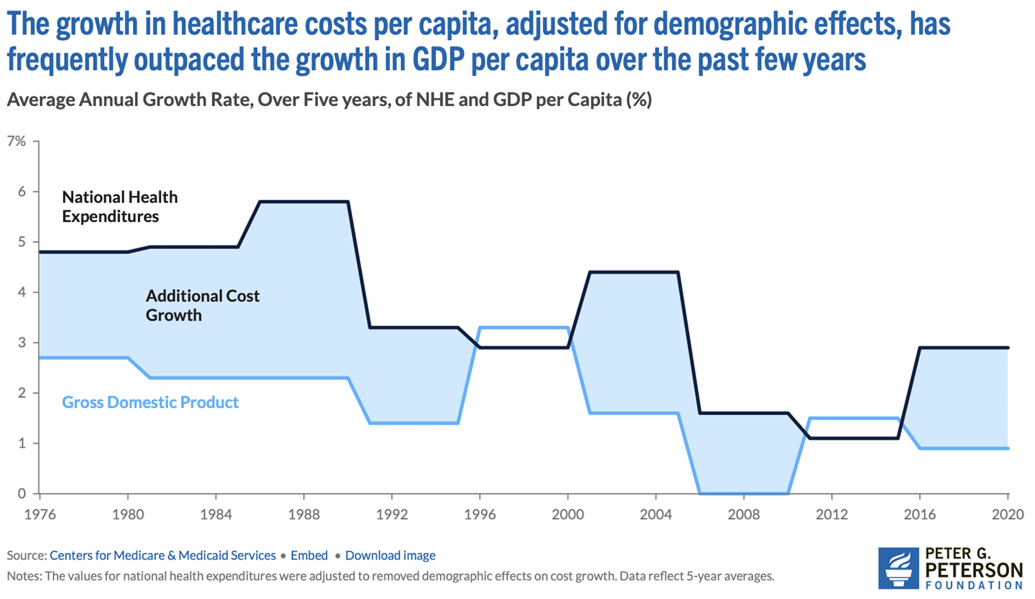

Healthcare Costs Are Outpacing GDP Growth

Over the past few decades, U.S. healthcare costs per capita have increased faster than GDP per capita, even after adjusting for demographic changes like an aging population. This gap has placed enormous pressure on federal budgets and strained rural health systems already struggling with limited resources.

The growth in healthcare costs per capita has frequently outpaced the growth in GDP per capita over the past few years.

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services via Peter G. Peterson Foundation

Federal Deficits Attributable to Health Care Are Rising Rapidly

The federal government has been increasingly relying on deficit spending to finance healthcare. Between 2018 and 2024, the amount of the federal deficit attributable to healthcare is projected to rise 83%, from $300 billion to $550 billion.

Federal healthcare-related deficit spending rose 83% between 2018 and 2024.

Peter G. Peterson Foundation

Supply, demand and costs continued to collide, making it ever more clear that the fiscal policies being used to finance the nation’s health care system are not just fiscally unsustainable, but are also adversely affecting the ability of consumers to get the care they needed and of providers to survive financially.

Cost Growth Is Driving Future Federal Healthcare Spending

By 2055, nearly half of the projected increase in federal healthcare spending will be due to cost growth, not population aging.

In 2036, the earliest year for which CBO reports such estimates, additional cost growth is projected to be 1.4 percentage points in Medicare. Medicaid, meanwhile, is projected to see a negative additional cost growth of -0.2 percentage points. By 2055, Medicare’s additional cost growth is projected to slow to 0.2 percentage points and Medicaid’s will grow to 0.6 percentage points. That means healthcare costs, adjusted for demographic changes, are projected to outpace economic growth in the federal healthcare system. That trend is primarily driven by factors such as rising medical prices and growth in real (inflation-adjusted) national income per person, as healthcare spending has traditionally risen with increases in income.

Health Care Challenges Adversely Affect:

- the ability to recruit and retain workers

- local and regional economic growth

- the funding of critical public health, safety, and educational services

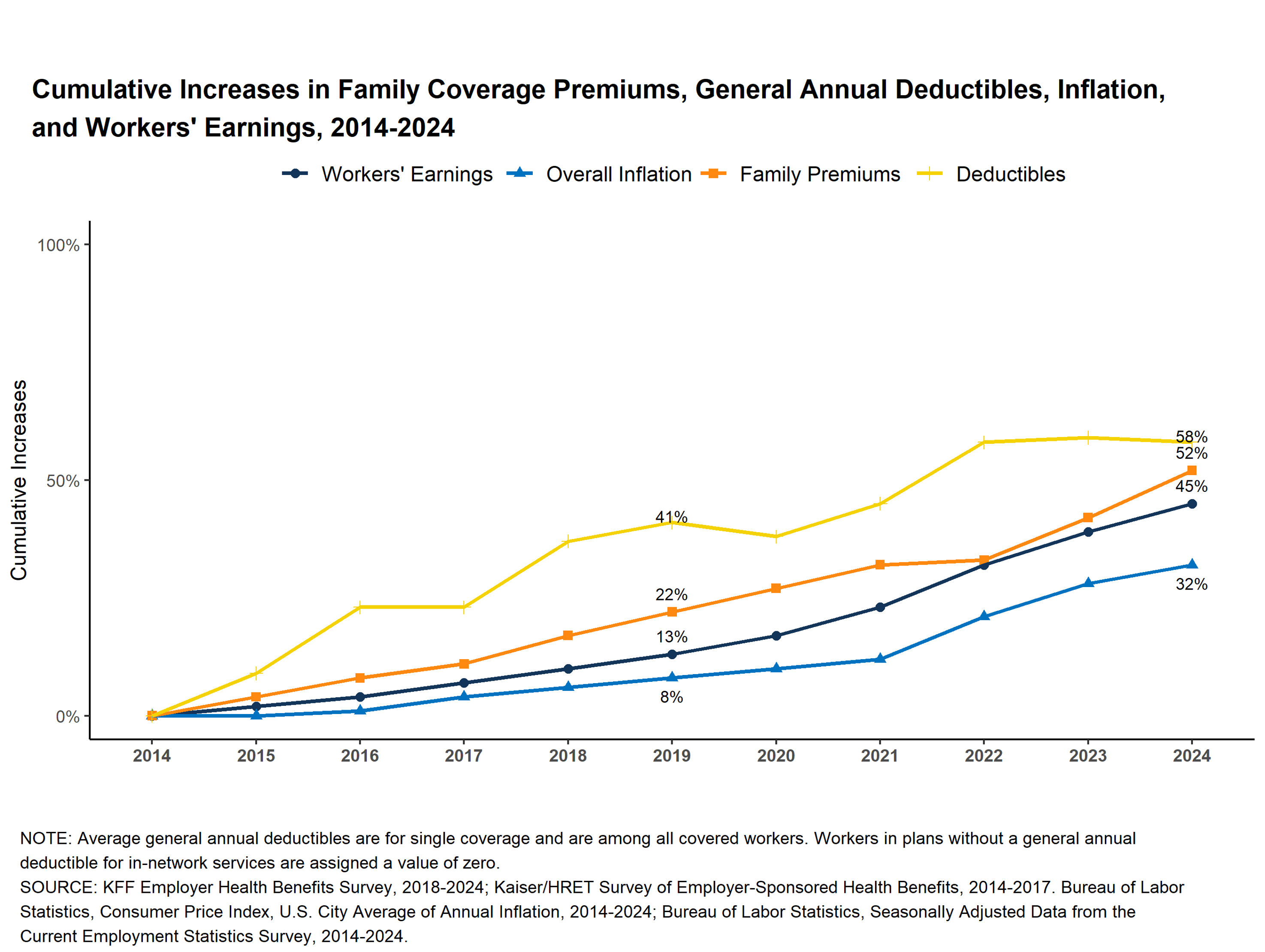

Between 1999 and 2022, worker wages increased 103%. Their out of pocket contributions for their health care increased nearly 300%, negatively affecting their take home pay and reducing discretionary spending.

KFF Employer Health Benefits Survey, 2018-2022; Kaiser/HRET Survey of Employer-Sponsored Health Benefits, 199-2017. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Consumer Price Index, U.S. City Average of Annual Inflation, 199-2022; Bureau of Labor Statistics, Seasonally Adjusted Data from the Current Employment Statistics Survey, 1999-2022.

Recent Hospital Closure Trends

The past five years (2020–2024) have been particularly devastating for rural healthcare. After relatively moderate closures in 2021 (7 hospitals), the numbers surged: 12 closures in 2022, 9 in 2023, and a dramatic spike to 38 complete closures by the end of 2024. This represents the highest single-year total on record, with 14 of those being Critical Access Hospitals. From 2017 to 2024, 62 rural hospitals closed compared to only 10 that opened, resulting in a net reduction of 52 hospitals. This trend has left 432 rural hospitals currently vulnerable to closure, with 46% of all rural hospitals now operating with negative margins.